The Magician's Nephew, by C.S. Lewis

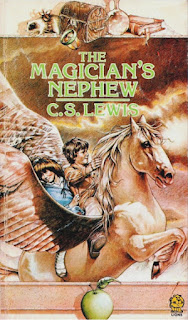

Here is a children's book, dating back to 1955, the sixth to be published in C.S.Lewis's fantasy saga of the magical land of Narnia. I've been doing a lot of nostalgic reading lately, and glancing back through my booklist I noticed I'd given this particular volume a 'star'; and I wondered why. A friend lent me a copy, in this edition (right). It's certainly not the first book I've read more than once, but this goes back to childhood, and I'm now looking at it through very different and much more aged eyes.

The Magician's Nephew is a prequel to the other Narnia stories, and therefore first in a chronological sense. Modern publishers tend to list it as 'Number One' in the series, but this is unfortunate. You don't have to be a serious critic to agree with almost all of them, that it's best to read the series in order of publication. There's a clear assumption in the text that you're already familiar with details of the characters and the landscape of Narnia. And on the other hand, there are various aspects of the world of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe which lose their impact if you've previously been introduced to them. There's a pleasure to one's recognition in The Magician's Nephew of, for instance, the origin of the lamp post in the snow, as one picks up on it straightaway, before it's spelled out for us. Conversely, on reading The Lion...etc., there's delight for the reader in Lewis's narrative, in encountering that same lamp post and wondering how on earth it can be. Of course, it isn't on earth, not ours anyway.

Many commentators feel that it's one of the weaker books; I must have felt otherwise; and one thing immediately obvious is the setting, of turn of the century London, which imparts a very different feel to the rest of the series, which has a distinctly 1950s sensibility. One imagines Lewis was thinking back to his own childhood. And in that booklist of mine, I see that not long before, I'd read a couple of books by E.Nesbit, and some similar books, and it makes complete sense that having been engrossed in those, I would like this. The children, the way they talk, and their adventures - well, at least at first! - are much the same, in the same Victorian/Edwardian world. By the time of my own childhood, maids and horse drawn carriages had long gone, but I knew houses like Digory's, and had aged relatives who sounded a bit like his - thankfully, none as troublesome as Uncle Andrew!

Something else I would have liked would have been Pauline Baynes' wonderful line drawings, and I was delighted to find that they are still included in editions of the book. Illustrators were often mocked as being 'not proper artists' but I only have contempt for that, and I especially admire the technique and the art of the very best illustrators. I've cheated, because the originals are pure black and white line drawings, and I've sought out these colourised versions. I also admit some doubt about Baynes' rendering of Jadis in the other illustration, below; her expression is really far too happy and carefree! Her whip and the distress of the horse, are a much better guide to knowing what Jadis is all about. But I love the exuberance and drama of the scene.

I freely confess to looking the book up on Wikipedia. Sometimes there's nothing of great interest, but in this case I was pleasantly surprised by not only the usual synopsis, but something of its publishing history, and some discussion of its themes. I'd recommend a read of it. However, the themes discussed are its Christian themes, and here I'd like to offer some thoughts about gender roles in the story.

I think, to Lewis, Polly and the various other female characters are given as much respect and sympathy as the males. And most do speak up for themselves, very forthrightly. While the main male villain, Uncle Andrew, is increasingly pathetic, Jadis is memorably intimidating. And she isn't a two dimensional villain, but fully rounded: we come to understand very well why she is as she is. As for the children, Polly is frequently assertive and capable of disagreeing with Digory, and she's often in the right. It's the traditional stereotype of girls being sensible, and boys sometimes being hot headed. Boys, and men, can be selfish, greedy, and rash when they're brave; girls tend to be healers, to be supportive, and resolvers of arguments.

Quite.

There's some truth to all stereotypes, but it would be ridiculous to use them as reliable guides to human nature. More to the point, The Magician's Nephew is strongly allegorical, and Lewis's decisions in this area are important. The book replays the Christian story of Creation, in particular the Temptation in the Garden of Eden, where it is Digory who is tested, not Polly. We can be glad that this time round, Eve is not created from Adam's rib, so to speak. But she is left outside, observing that it is not right for her to enter the Garden. I suppose Lewis realised that if Polly was present, her voice of reason would reduce the tension of Jadis's temptation.

Yes, I fully appreciate that in many ways, Lewis actually puts women on a higher pedestal than men. Jadis isn't the only strong character in the story; both Polly and Aunt Letty are portrayed with that very English streak of stoic toughness. But the story is left to men. In Lewis's world, the drama of history is a male preserve, I suspect. When Aslan installs cabby Frank as the first King of Narnia, his wife is magicked into the scene just like that, and merely to prop him up. It's not that any disrespect is shown her; but it is all about him. And when Aslan organises a council of the creatures of Narnia, they're all males, human or otherwise. And Polly, for all her interest as a character, and her contribution to events, is in the end only a part player in Digory's story.

Yes, I fully appreciate that in many ways, Lewis actually puts women on a higher pedestal than men. Jadis isn't the only strong character in the story; both Polly and Aunt Letty are portrayed with that very English streak of stoic toughness. But the story is left to men. In Lewis's world, the drama of history is a male preserve, I suspect. When Aslan installs cabby Frank as the first King of Narnia, his wife is magicked into the scene just like that, and merely to prop him up. It's not that any disrespect is shown her; but it is all about him. And when Aslan organises a council of the creatures of Narnia, they're all males, human or otherwise. And Polly, for all her interest as a character, and her contribution to events, is in the end only a part player in Digory's story.

I say again, that I don't question Lewis's admiration and respect for women. More than that, girls and women in his stories often take leading parts at times. Just as in the War against tyranny which Lewis had just experienced, women had risen to the occasion in all sorts of capacities, ably taking men's places. I simply feel that for Lewis, there's maybe a right and fitting place for men and women in a well ordered (Christian) world. After the War, women went back home again to raise families as if nothing had changed. The story of history is still men's history today, isn't it?

This has ended up sounding like an attack on Lewis, which I don't mean at all. His values are those of his time. He's a very good writer. There is poetry in his prose, and beauty in his ideas, when as in the scene of Temptation, he sets about dramatising his moral arguments. You would think, wouldn't you, that you'd never be tempted? Lewis cleverly puts you in Digory's shoes, and makes you more than a little uncertain about that.

Yes, I still like The Magician's Nephew.

The Magician's Nephew is a prequel to the other Narnia stories, and therefore first in a chronological sense. Modern publishers tend to list it as 'Number One' in the series, but this is unfortunate. You don't have to be a serious critic to agree with almost all of them, that it's best to read the series in order of publication. There's a clear assumption in the text that you're already familiar with details of the characters and the landscape of Narnia. And on the other hand, there are various aspects of the world of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe which lose their impact if you've previously been introduced to them. There's a pleasure to one's recognition in The Magician's Nephew of, for instance, the origin of the lamp post in the snow, as one picks up on it straightaway, before it's spelled out for us. Conversely, on reading The Lion...etc., there's delight for the reader in Lewis's narrative, in encountering that same lamp post and wondering how on earth it can be. Of course, it isn't on earth, not ours anyway.

Many commentators feel that it's one of the weaker books; I must have felt otherwise; and one thing immediately obvious is the setting, of turn of the century London, which imparts a very different feel to the rest of the series, which has a distinctly 1950s sensibility. One imagines Lewis was thinking back to his own childhood. And in that booklist of mine, I see that not long before, I'd read a couple of books by E.Nesbit, and some similar books, and it makes complete sense that having been engrossed in those, I would like this. The children, the way they talk, and their adventures - well, at least at first! - are much the same, in the same Victorian/Edwardian world. By the time of my own childhood, maids and horse drawn carriages had long gone, but I knew houses like Digory's, and had aged relatives who sounded a bit like his - thankfully, none as troublesome as Uncle Andrew!

Something else I would have liked would have been Pauline Baynes' wonderful line drawings, and I was delighted to find that they are still included in editions of the book. Illustrators were often mocked as being 'not proper artists' but I only have contempt for that, and I especially admire the technique and the art of the very best illustrators. I've cheated, because the originals are pure black and white line drawings, and I've sought out these colourised versions. I also admit some doubt about Baynes' rendering of Jadis in the other illustration, below; her expression is really far too happy and carefree! Her whip and the distress of the horse, are a much better guide to knowing what Jadis is all about. But I love the exuberance and drama of the scene.

I freely confess to looking the book up on Wikipedia. Sometimes there's nothing of great interest, but in this case I was pleasantly surprised by not only the usual synopsis, but something of its publishing history, and some discussion of its themes. I'd recommend a read of it. However, the themes discussed are its Christian themes, and here I'd like to offer some thoughts about gender roles in the story.

I think, to Lewis, Polly and the various other female characters are given as much respect and sympathy as the males. And most do speak up for themselves, very forthrightly. While the main male villain, Uncle Andrew, is increasingly pathetic, Jadis is memorably intimidating. And she isn't a two dimensional villain, but fully rounded: we come to understand very well why she is as she is. As for the children, Polly is frequently assertive and capable of disagreeing with Digory, and she's often in the right. It's the traditional stereotype of girls being sensible, and boys sometimes being hot headed. Boys, and men, can be selfish, greedy, and rash when they're brave; girls tend to be healers, to be supportive, and resolvers of arguments.

Quite.

There's some truth to all stereotypes, but it would be ridiculous to use them as reliable guides to human nature. More to the point, The Magician's Nephew is strongly allegorical, and Lewis's decisions in this area are important. The book replays the Christian story of Creation, in particular the Temptation in the Garden of Eden, where it is Digory who is tested, not Polly. We can be glad that this time round, Eve is not created from Adam's rib, so to speak. But she is left outside, observing that it is not right for her to enter the Garden. I suppose Lewis realised that if Polly was present, her voice of reason would reduce the tension of Jadis's temptation.

Yes, I fully appreciate that in many ways, Lewis actually puts women on a higher pedestal than men. Jadis isn't the only strong character in the story; both Polly and Aunt Letty are portrayed with that very English streak of stoic toughness. But the story is left to men. In Lewis's world, the drama of history is a male preserve, I suspect. When Aslan installs cabby Frank as the first King of Narnia, his wife is magicked into the scene just like that, and merely to prop him up. It's not that any disrespect is shown her; but it is all about him. And when Aslan organises a council of the creatures of Narnia, they're all males, human or otherwise. And Polly, for all her interest as a character, and her contribution to events, is in the end only a part player in Digory's story.

Yes, I fully appreciate that in many ways, Lewis actually puts women on a higher pedestal than men. Jadis isn't the only strong character in the story; both Polly and Aunt Letty are portrayed with that very English streak of stoic toughness. But the story is left to men. In Lewis's world, the drama of history is a male preserve, I suspect. When Aslan installs cabby Frank as the first King of Narnia, his wife is magicked into the scene just like that, and merely to prop him up. It's not that any disrespect is shown her; but it is all about him. And when Aslan organises a council of the creatures of Narnia, they're all males, human or otherwise. And Polly, for all her interest as a character, and her contribution to events, is in the end only a part player in Digory's story.I say again, that I don't question Lewis's admiration and respect for women. More than that, girls and women in his stories often take leading parts at times. Just as in the War against tyranny which Lewis had just experienced, women had risen to the occasion in all sorts of capacities, ably taking men's places. I simply feel that for Lewis, there's maybe a right and fitting place for men and women in a well ordered (Christian) world. After the War, women went back home again to raise families as if nothing had changed. The story of history is still men's history today, isn't it?

This has ended up sounding like an attack on Lewis, which I don't mean at all. His values are those of his time. He's a very good writer. There is poetry in his prose, and beauty in his ideas, when as in the scene of Temptation, he sets about dramatising his moral arguments. You would think, wouldn't you, that you'd never be tempted? Lewis cleverly puts you in Digory's shoes, and makes you more than a little uncertain about that.

Yes, I still like The Magician's Nephew.

I listened to all of these as audiobooks with SIimon about 10 years ago...(aswell as reading them and seeing the BBC version as a child myself) they get progressively stranger but kept his attention and mine. What a strange parallel universe they create, especially the Last Battle....

ReplyDeleteIndeed. I always liked well imagined worlds. But I think Lewis's appeal was his characters, and the way he wrote them into testing situations, often with a moral element. Situations in the stories repeatedly tempt the children to take an easier path, or towards speedier gratification. ...It's bizarre to me now, that it was The Last Battle which I read first. But I also think that the order you read them in doesn't matter quite as much as it does in most such series.

Delete